In my last post, I talked about how the

It is somewhat disturbing that the chosen 'cure' for the Western debt problem is more debt.

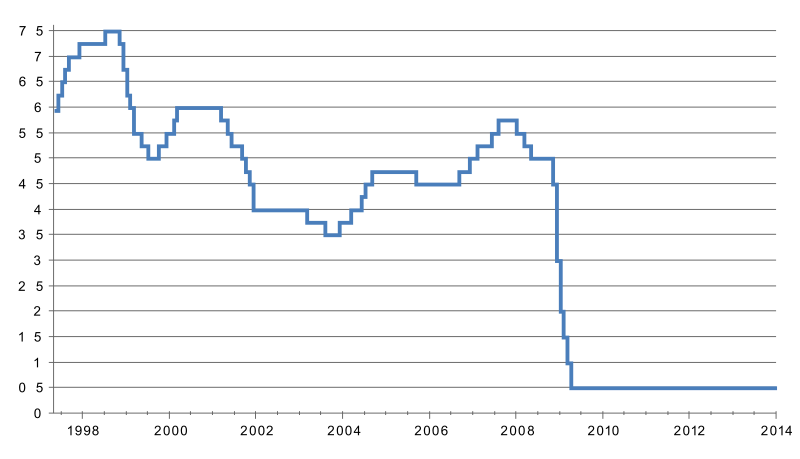

The Bank of England base rate has been slashed to 0.5%, the

Lower interest rates = more incentive to get into debt = more debt = bigger problems down the road.

As well as incentivising debt, low interest rates also damage cash based investment returns. What is the point in having money in the bank earning 1.5% interest, when inflation is running at 3%? You are technically losing money. This doesn't just affect the rich, it affects everyone (who has a pension or savings). Pension funds need exposure to dependable cash based investments, low interest rates are damaging the returns on these investments leaving less money for people to retire on. Also annuity rates are linked in part to interest rates and as such are very low right now.

People retiring now who have been prudent and saved their whole lives are facing a double whammy of diminished pension pots and bad value from annuities. This will have a long term detrimental effect on the economy as their spending in retirement will be curtailed.

As our debts increase, our sensitivity to a rise in interest rates also increases, making it harder to return to a situation of normality.

I'm not suggesting a swift hike in rates as that could be very damaging. Rather a gradual elevation of about 0.5% a year.

The sooner we get ourselves off the faux life support system of cheap debt, the better our chances of a sustainable recovery.